Every morning during wound care, a line of boys comes into the clinic. They’re all of different ages, but you couldn’t tell; unless their wounds are fresh, they’re all laughing and joking with each other, whether they’re 80 or 8. (RICHTER!!!!) They’re funny little things, and they use the same verve that got them into trouble to carry them through it.

They’ve got wounds everywhere on their bodies, but it’s the expendable limbs that get hit the worst – the stuff that flails about and gets banged up, likes legs, and arms, and heads. A frequent source of fresh injuries is the bicycle; children sit on the back, and their legs dangle; soon enough a leg gets caught in the spokes, and a new boy limps into my clinic.

Dinka boys try not to acknowledge pain. They can’t, or their mother or father (or in fact anyone who happens to wander by) will shush them up. One of my favourites, Wur, got pushed by another playful boy into a machine for grinding groundnuts. When his mother brought him here, he was quietly holding his bloody, mangled hand. He barely winced as we cleaned and examined it. He didn’t cry until we began to amputate his finger – I guess he was hoping we could save it, and was distraught when he saw we couldn’t. But now, he greets me with a smile every day, and stalked me to church once (now I’ve just got to get him inside it). His wound is healing well, and I’m sure to say “apath apei” (“very good”) whenever I remove the bandage.

Once, I removed the bandage of an older boy who spoke English. As I cleaned it, I was very careful, sponging instead of scrubbing, to avoid tearing the tender new flesh. He took it as an insult, demanding why I was being so soft with him. He must have been surprised when I laughed aloud at that. If only he had seen me in Basic Training; then he would know how hard I can be on my boys.

Sabet’s nephew is younger than the general crew. He has Sabet’s name, and Kate and I call him “Ka-Sabet” (“ka” is a prefix for “small” in Swahili); and he’s perpetually in here. As his broken arm heals, he breaks his toe. As his broken toe heals, he tears the nail off. But he HATES the clinic. Several men have to carry him inside if he even suspects he’s getting an injection; I once followed him around for 15 minutes promising “tuom alieu” (“no injection”) when I only wanted to wipe his wound clean. He trusts me now, but I wouldn’t dream of being the one to give him an injection ever; he has, reserved just for them, the most piercing scream on the planet, in all the ages that have passed and all that will ever be. All my other boys cover the ears and giggle, and all the patients waiting outside wonder what we’re doing to the child.

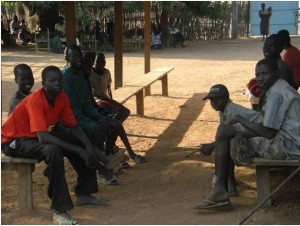

And then, of course, there’s Superdude. For the longest time I didn’t know his name, and didn’t want to; you’ll agree that Superdude is quite apt, if you look at the picture at right. He wears a cape tied round his shoulders, and he uses a cane – it’s probably his crime-fighting weapon, and the limp is just for show. When he first gashed open his shin, he sat on the line all day, waiting his turn, even though it counted as an emergency and he could totally have been seen first. And Superdude is perpetually telling us how to dress his wound. For some time, he kept demanding an injection because he thought it would speed his recovery. Finally I stuck him with a very painful (but very effective) drug. I couldn’t help giggling as his limped away, mewling; it must be his Kryptonite.

You would think it would be hard to get my ka-boys to show up every single morning to have someone poke and prod at their wounds. Here’s the secret; as much as I like boys, they also like me. I smile at them, and learn their names; when I’m cleaning their wounds, I sing and talk with them, helping them with their English, and learning Dinka from them. Soon I’ll be proficient enough to discuss sports :-). They jostle one another for the chance to have me be the one to dress them. I haven’t got them trading valuables for the privilege yet, but give me time… though I suppose I’ll need candy to accomplish that feat…

And none of them know that whenever they win, and I’m their wound-dresser, I’m really just looking for an excuse to lay hands on them and pray for them. Their wounds will heal without my prayers, and they’ll go back to their normal lives; but I pray that their lives will never be normal again. If you get a chance to be one of my boys, I pray that one day you’ll become one if His boys too. And so I spend the rest of the day with people of all ages, most of them pregnant women. And I wait patiently for the next morning, so again I can see, and smile at, and serve, and pray for, my rambunctious, goofy, shy, outspoken, never-seem-to-learn, always-have-learned-something-new, laughing, wonderful, hilarious boys.